CPDSF III, Kyoto

Captain’s Log: Stardate 60706.5

The crew has arrived at an important waypoint in our quest to understand planetary system formation. The Circumplanetary Disks and Satellite Formation (CPDSF) III conference, held in Kyoto, Japan, gathered experts from across the quadrant to review the current status of circumplanetary disk (CPD) research—one of the most crucial yet challenging frontiers in planetary science.

Briefing: Key Research Highlights

CPD Observations: Charting the Unseen

Commander A. Isella led a comprehensive review of CPD observations. Despite numerous attempts to detect new CPDs beyond the landmark discovery of the CPD around PDS 70c, success has remained elusive. The frontier remains difficult to breach, and currently, the strongest CPD candidates include HD 169142 b, Delorme 1 (AB) b, and SR 12 AB c. However, as with all observational challenges, advancements in technology may soon turn the tide. Instruments such as Metis/ELTs and ngVLA offer hope for future breakthroughs.

The search for exomoons through transit timing variations (TTV), radial velocity (RV), and direct imaging was also discussed. Yet, despite substantial efforts, no confirmed detections have been made. It is clear that these missions require advanced instruments and long-term monitoring before we can confidently detect exomoons beyond our Solar System.

Infrared line diagnostics (H-alpha, Pa-beta, Br-gamma fluxes) remain a challenge. Current technology limits the detection of accretion shocks to planets of 10 Jupiter masses or larger, meaning that all observed flux is likely from the CPD itself, rather than the planet.

CPD Theory: The Mechanics of Moon-Birthing Disks

Dr. Judit Szulágyi provided a commanding overview of CPD theory, detailing the conditions necessary for their formation:

- CPDs emerge when cooling times are short, favoring massive planets beyond the ice line, which can support a satellite system.

- If cooling times are longer, the result is a circumplanetary envelope rather than a full-fledged CPD, meaning no large moons will form.

- Initially, CPDs are hot and optically thick, evolving rapidly until they cool to ice-freezing temperatures and become optically thin.

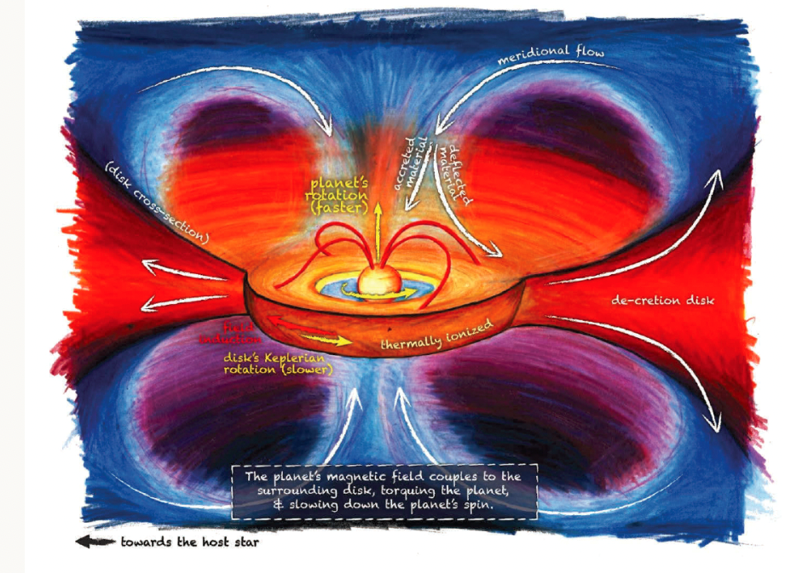

- Meridional circulation, driven by planetary spiral wakes, continually feeds the CPD with material from the parent circumstellar disk (CSD).

- The presence or absence of a cavity between the planet and CPD depends on whether the system operates as a magnetospheric accretor or boundary-layer accretor—a question that ongoing observations may soon resolve.

Satellite Formation: A Tale of Two Giant Planets

The formation of moons is not a uniform process across planetary systems. Not all moons form within CPDs—different mechanisms exist:

- CPD formation: Moons form directly within the circumplanetary disk, such as the Galilean moons of Jupiter.

- Capture events: Some moons, like Triton of Neptune, Phobos and Deimos of Mars, were likely captured from elsewhere.

- Planet-planet interactions: Our own Moon may have originated through a giant impact rather than CPD accretion.

Several reports focused on Jupiter and Saturn’s satellite systems, which present a stark contrast in their formation histories. Jupiter’s four Galilean moons are similar in size and composition, indicating a well-structured CPD formation process. In contrast, Saturn’s moon system is dominated by Titan, with many smaller moons in irregular orbits.

A key issue raised was why Titan appears to have formed differently from Jupiter’s moons. The leading hypothesis suggests that while Galilean moons could form through a pebble accretion scenario, a similar process fails for Titan—theoretical models predict that pebbles should have fallen into Saturn rather than forming moons. The presence of a properly sized cavity in Saturn’s CPD may have prevented this material from being lost, allowing Titan to grow. However, much remains unknown about the formation of moons in our own Solar System, let alone exomoons around distant planets.

Final Reflections

This conference provided invaluable insights into both observational and theoretical advancements in the study of circumplanetary disks and satellite formation. While the field remains fraught with challenges, the continued push for more powerful instruments and refined models ensures that progress is on the horizon.

As the mission concludes, one thing is clear: the story of planetary formation is far from fully written. The next frontier in the search for CPDs and exomoons awaits.

Captain out.